RIKLBLOG

|

| Tomorrow |

| 01 March 2023 |

| Yesterday |

| Index |

| Eventide |

| SETI League |

| PriUPS Project |

| Bonus! |

| Contact |

With Apologies to Ted Baxter

It all began at an enormous 50,000 Watt radio station in New York City. It was my pleasure and privilege to be working at the largest* radio station in the United States, and possibly in the world. This blog has referred to my stint at WABC on several occasions, and the few years I was employed there engendered a lifelong affection for broadcasting and all her manifestations and eccentricities**.

Unlike the small radio station at which Ted Baxter worked, WABC was large in other ways. One of them was monetarily. Radio stations make their money by selling advertising, WABC charged a lot! Advertisers make their money by selling products and services, and hope the advertising for which they paid so dearly increments their sales and hence their lucre. But while the cost of advertising is known, it's value is often a mystery. Advertisers give the radio station money and cross their fingers. Sometimes ads are successful, sometimes they run a couple of times and elicit no detectable response. Ad agencies and radio stations offer many explanations for this, but the advertisers—the ones actually out the money—have other suspicions. One is wondering whether their ad actually ran on the air at all. Unlike newspaper and magazine ads which are easy to verify*** by inspection, few advertisers either know precisely when their ad was run, had the technology to record it, or can prove that it had a flaw affecting its efficacy. Since the radio station had many advertisers and issues like this came up frequently, the simplest (if not simple) solution was for the station to make an audio recording of its programming, 24 hours per day, 365 days per year. For decades.

The cost of recording wasn't trivial, but it was also justified for other reasons. For example, there was the small matter of the station potentially losing its FCC license to broadcast. Despite the family-friendly language of this blog, I suspect thousands of my millireaders know what I mean when I use the expression "the F-word" or even, with trembling fingers, the "N-word." Not to mention "the C-word." Are there more? Do we not have an alphabet? Let any of these words or their variations slip into an open microphone and Forces for Good in the community, and perhaps the FCC, won't let them past the ionosphere without visiting tribulations upon the station and all who sail in her.

And there's always slander. Accuse someone of something vaguely illicit, and the lawyers emerge from the loam. Having a recording as evidence that it wasn't said, or was at least taken out of context, might save the station years of legal turmoil and prevent some hapless sport or news announcer from spending the rest of his career writing in Europe. In summary, both for monetary reasons and protection from government and private litigation, recording the station and archiving the recordings was a Good Idea.

If You're Old Enough

Or if you ever watched a movie or television, you might remember the "tape recorders" of yore. They used coated plastic tape, 1/4-inch wide, generally on reels from 3 to 14 inches in diameter. The coating was typically of some chemical variant of rust (iron oxide) that could be magnetized by a variable magnetic field whose strength was controlled by the audio signal of the radio station. By selecting the speed of the tape over the "record head," one could achieve audio quality varying from extremely good to a version of "the S-word." Since the goal was to memorialize words that were said on the radio station, the quality only had to be adequate for that purpose, and not for music. Problem solved, but not well enough. If one's intention was to archive decades of recordings, one would require many rooms to store the tens of thousands of dollars worth of tapes.

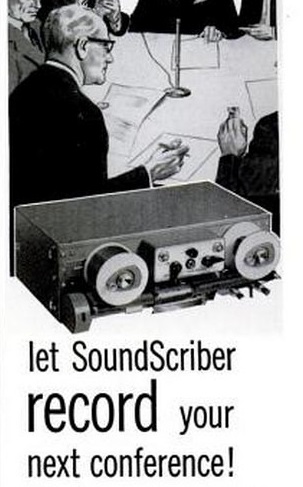

Enter the Soundscriber

A partial solution and salvation came in a variant form of the videotape recorder. VTRs used a clever scheme to record more densely sound and video. They used wider tape—inches instead of fractions—and, while moving the tape at a reasonable speed moved the magnetic recording head over the tape much faster. For audio, which carries much less data than does a video signal, the recorder could move the tape more slowly still, to the extent that a reel of tape only a few inches in diameter could store an entire day of radio!

|

|

The wide but small-diameter tapes could capture a full day's worth of WABC programming. Although the ad touts it for recording conferences, it worked just as well for radio, although the music quality was appalling. It did have one flaw, however, that was pretty serious for use in a fast-paced radio environment. If you wanted to find the allegedly missing ad, a bit of slander in an hour-long talk show, or one of those elided words, It was a challenge. |

Why?

While employed at the station, my own experience with the Soundscriber encompassed the late '60s, I don't know what fraction of its timeline I intersected. But the late '60s preceded digital technology, with this consequence:

It Was Difficult and Tedious to Find Your Target on the Tape!

The tape was 24 hours long. Looking for that advertisement at 13:03:40 meant going a bit more than half way from the beginning to the end and then listening for a random time check or comparing it to the log—imprecise, if even extant—and eventually finding it after five to 10 minutes of searching. Boring! Tedious! But necessary, since the tape and the whole system was analog, with no concept of clock time. If somehow the hand-written tape label was missing or wrong? Doom!

Fortunately, we station staffers weren't called upon daily to commit audio archaeology. When I left the station, my memory of the Soundscriber was sublimated until this very blog. Let's "fast forward," now, for about two decades, and many cubic metres of ancient tape recordings.

The Era is Now Digital, and Eventide Had an Idea

Thinking of potential broadcast products beyond the famous Eventide profanity delay, we decided to consider making a product that would make logging radio a trouble-free cinch. Technical developments allowed weeks and then months of broadcast programming on a small "DAT," roughly the size of an audio cassette tape.

- No longer did you need rooms, or large cabinets to store media. Years would fit in a shoebox.

- No longer did you have to spend many minutes searching for an ad or other program issue. Just type the time on a keyboard and it would be found automatically.

- Want to hear what your competitors were up to? The original product offered up to 24 audio channels of decent quality audio. You could record your entire market, along with the newsroom telephones and more.

When we announced our new recorder <FICTION> the broadcast world was remarkably enthusiastic, we got calls from almost all the major stations nationwide and overseas, and the product flew off the shelf. Like the profanity delay before it, this recorder filled an important need and the broadcast world was abuzz with talk about this innovative product.</FICTION>

I took the opportunity to use my proprietary FICTION HTML tag because the above two sentences are lies. In fact, almost no stations had the budget to buy the logger, they already had a PC that they thought could do the job, and apparently weren't all that interested in recording anyway. We sold a few here and there, managed to contain our disappointment, and went on with life and our other, better received, products.

Until Late One Fateful Afternoon!

I happened to pick up the telephone and found myself speaking to a representative of Dictaphone, the storied voice recording division of Pitney Bowes. They had a line of products that still used 14-inch reels that were used by the thousands in police stations and surveillance vans throughout the land. The gist of the telephone call was "would Eventide be willing to manufacture these new recorders under the Dictaphone brand"?

I recall thinking—and my dislike of extravagant typography prevents me from using the font this deserves—

YES!

And that, in a blogsworth of words, explains how Eventide became, now after three additional decades, the premier manufacturer of logging recorders for public safety. (And, I think, we may have even sold a few to radio stations along the way.)

* Largest in terms of listeners. We took up a couple of floors at 1330 Avenue of the Americas in New York City, and also had a transmitter site in Lodi, New Jersey. This was not the Lodi of "Back in Lodi Again" but it often felt that way to me when I had transmitter duty.

** Here are a few: The Heen and the Hern, Memories of Dan Ingram, and even the Union Water Pitcher .

*** Remind me to tell you the story of a scam-magazine that had no circulation except to the advertisers themselves!

| © 2023 |

| Richard Factor |

NP: "Edward (The Mad Shirt Grinder)" Quicksilver Messenger Service |

( |

ToTD Unlike most of my audio-company T-shirts, obtained in trade from long forgotten companies and traveling bands, this one has Significance. Bruce Martin, the owner of Martin Audio, was a friend and a booster of our company in the early days. He died in a bizarre and tragic accident. |

|